Company men

The U.S. Chamber flexes its new political muscle

By Peter Hamby, CNN National Political Reporter

Washington (CNN)

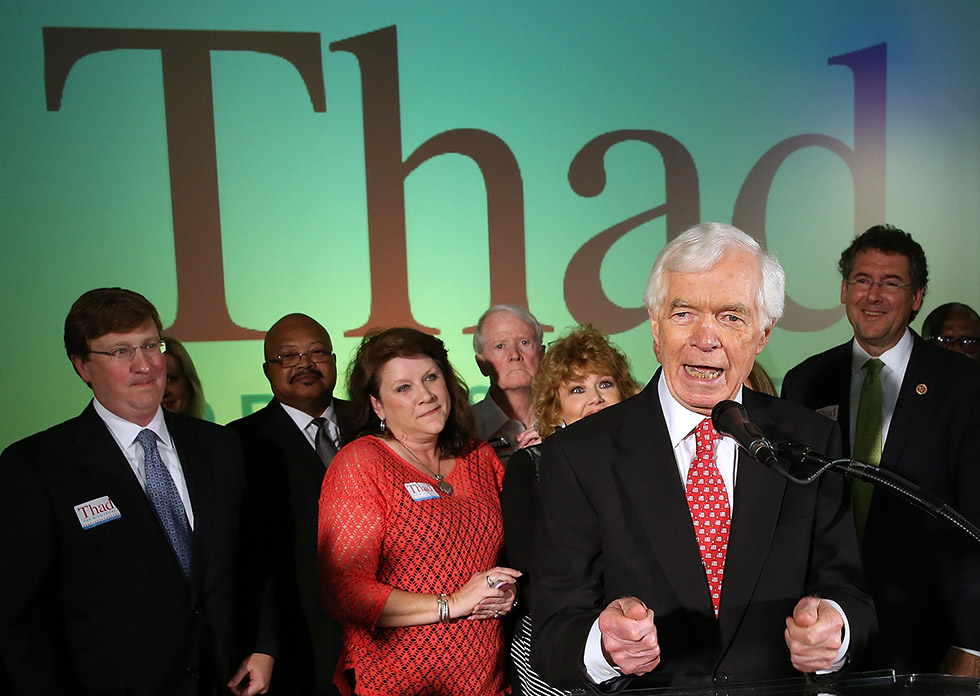

The plot to save Thad Cochran was hatched at Off The Record, the subterranean bar inside the Hay-Adams hotel in downtown Washington.

In mid-June, just days before the Mississippi Senate runoff election, Tom Donohue, the hard-nosed CEO of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, was commiserating over drinks with Scott Reed, his senior political strategist, and Chip Pickering, a former Mississippi congressman-turned-telecom lobbyist.

The trio were smarting. After racking up an enviable 10-0 winning streak in midterm races, Mississippi voters dealt the powerful business lobby a major blow: Cochran, a Senate stalwart supported by the Chamber and its allies in the Republican establishment, had stumbled in his primary battle with Chris McDaniel, a smooth-talking state senator backed by tea party groups. The two Republicans were now facing off in a three-week duel that, to many, looked like a lost cause. American Crossroads, the Karl Rove-backed GOP group that had been supporting Cochran, announced that it was pulling out of the race.

Making matters worse for Donohue and his colleagues, McDaniel was a hated trial attorney, a specimen Chamber-types have viewed with blood-curdling contempt.

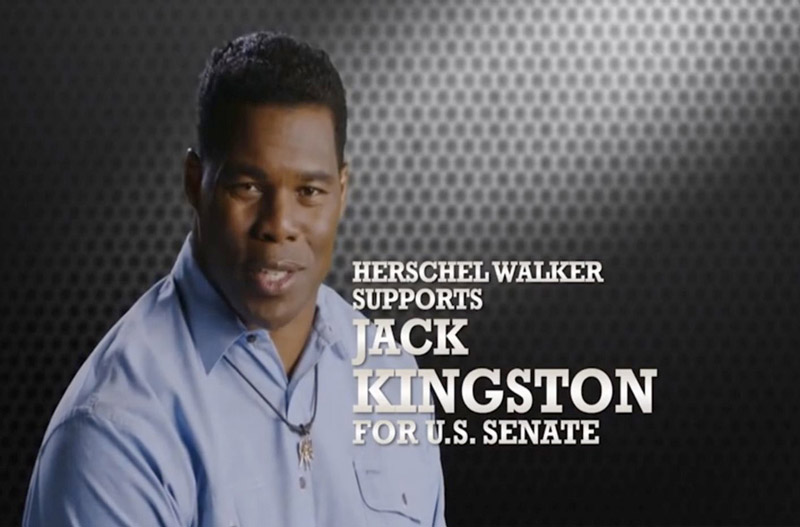

A key element of the Chamber's playbook this cycle is tapping big-name endorsers to star in television commercials for their preferred candidates. Reed and Engstrom recruited Jeb Bush, Mitt Romney and Marco Rubio to appear in ads, but they've also looked beyond politics. In Georgia, they booked college football hero Herschel Walker to appear in an ad endorsing Jack Kingston.

The Chamber team was scrounging around for ideas, desperate for a silver bullet that might alter the course of the campaign. In other races, they'd enlisted famous Republicans like Mitt Romney and Jeb Bush to star in television ads for their favored candidates. The formula had paid off. In the Georgia Senate race, they looked beyond politics, convincing Herschel Walker, the iconic University of Georgia football hero whose in-state star power is second only to Jesus, to cut an ad supporting Jack Kingston, the Chamber-backed candidate.

They needed something similar in Mississippi. That's when Pickering, an acquaintance of former NFL quarterback legend and southern Mississippi native Brett Favre, piped up.

"I think I can get to Brett," Pickering said.

Reed pulled out his cell phone immediately and thrust it across the table. "Call him."

The idea set off a madcap scramble to locate Favre, convince him to get involved in a political campaign, and produce a television ad compelling enough to pierce the political clutter on TV and sway new voters who hadn't participated in the primary, which Cochran lost by only 1,400 votes. An initial survey of the runoff, conducted in the days after the June 3 primary by Chamber pollster Tony Fabrizio, showed Cochran trailing McDaniel by eight points.

"We knew the clock was ticking," Reed recalls. "Our strategy was to grow the electorate. It was the only way to win. We knew if it was a closed primary, we would have lost. So we made a play for Reagan Democrats. Bubba. And who better than Brett? Especially in southern Mississippi where he is an icon, and where Thad had underperformed."

It took three days to track down Favre, who was out of the state on vacation. The Chamber also sought out Eli Manning, another NFL standout who starred at Ole Miss. But he passed on the idea. By Monday, just eight days before the runoff, Favre agreed to shoot a pro-Cochran ad on his farm near Hattiesburg. Favre's parents were schoolteachers; they sold him with Cochran's promise to protect federal education funding.

"Brett is not a political guy," says Rob Engstrom, who, along with Reed, helms the Chamber's political operation. "But when we talked to him about it, he looked at it and said, 'This is about our state.' It appealed to him. He said yes right away."

Back at Chamber headquarters in Washington, across the street from the White House, Reed and Engstrom scrambled the jets.

Their go-to film crew drove through the night across the Gulf Coast from Pensacola, Florida, to Hattiesburg. Their creative director caught a seat on the last flight south out of Dulles. Tuesday morning was spent shooting the commercial on Favre's 460-acre farm.

Satisfied with the footage, the film crew flew back to Washington that night. The ad was in edit the next morning, and by Wednesday night the commercial — which showed Favre sitting on the bed of a truck, telling viewers that "Thad Cochran always delivers" — was shipped to television stations in Mississippi. The Chamber put $100,000 behind the spot every day for the final six days of the campaign.

Brett Favre, who grew up near Hattiesburg, starred in a Chamber-produced TV spot for Thad Cochran in Mississippi that saturated airwaves in the state for the final week of the runoff election. "Brett is not a political guy," Engstrom said of the ad. "But when we talked to him about it, he looked at it and said, 'This is about our state.' It appealed to him. He said yes right away."

Cochran pulled off a miracle, winning in narrow and dramatic fashion by only 6,700 votes — a result still being disputed by a flabbergasted McDaniel campaign.

It wasn't the Chamber's ad alone that did it. The Cochran campaign made a concerted push to grow turnout after the primary, a push that involved recruiting African-American voters and Republicans who might have otherwise stayed home. Other outside allies coordinated to do the same. But the Chamber's role in helping drag Cochran over the finish line is undisputed.

"The guys at the Chamber are pros," says Henry Barbour, a veteran GOP operative and Cochran supporter who ran a super PAC supporting the candidate. "They helped orchestrate an overall strategic effort that at the end of the day helped Sen. Cochran close the margins and win the election."

The Mississippi runoff was a signal moment for the Chamber in what's quickly becoming the most aggressive political cycle in its 102-year history.

The conservative-leaning outfit, known mainly for its heavyweight policy and lobbying practices — it spent $74 million on lobbying in 2013, according to the Center For Responsive Politics — has emerged as one of the most powerful actors in American political campaigns, with roughly $17 million spent so far on Senate and House races, all of it on behalf of Republicans friendly to the business community.

In doing so, the Chamber has planted itself firmly on the front line of the GOP establishment's push to extinguish tea party ideologues wherever they threaten business-backed candidates — in Mississippi, Alabama, Ohio, Kentucky, and elsewhere.

"The crowd that wants to come to Washington and blow the place up and shut the place down, that's a threshold issue for us," Reed says. "We care about governing."

The world's largest business federation spent roughly $50 million on behalf of candidates in 2012 — and officials say they plan to blow past that total this year. The spending doesn't quite rival the midterm budget of other political entities like the conservative Koch brothers network, which reportedly plans to spend almost $300 million this election year, or even the $100 million being wielded by Tom Steyer, the San Francisco-based billionaire environmentalist.

But the Chamber's campaign footprint in 2014 represents a huge strategic shift for an ostensibly nonpartisan trade association that long trafficked in white papers, legal fights and lobbying pushes.

"They have clearly upped their game," said Tim Pawlenty, the former Minnesota governor and GOP presidential candidate who now heads the Financial Services Roundtable. "They have dedicated more resources, and deployed more resources on a targeted basis. They've gotten involved earlier, being more aggressive and bold in picking their candidates."

In Mississippi's Republican Senate primary, Sen. Thad Cochran pulled off a miracle in his runoff fight with tea party-backed Chris McDaniel by expanding the pool of GOP voters from the low turnout June primary. Cochran allies credit the Chamber for producing a television ad starring football legend Brett Favre, a Mississippi native who endorsed Cochran late in the race.

The Chamber is hardly a new player in political campaigns, having dabbled in elections up and down the ballot statewide and federally for the better part of two decades, usually backing Republicans over Democrats in general election contests, late in the race rather than early, and never taking sides in primaries.

But Chamber officials say the business community's growing exasperation with Washington intransigence demanded a juiced-up political program this cycle – both in Republican primaries and with early advertising salvos against targeted Democrats.

"We just can't take for granted anymore that good people will run for office and that they will win," says Rich Studley, the Michigan Chamber of Commerce CEO.

The old Chamber wisdom was that governing and campaigning were more or less distinct enterprises, in which the lobbyists and wonks handled business downtown while the political team did its best to assist its favored candidates every election year.

Today that sounds naïve.

No longer can the Chamber dabble late in political races and hope to shape policy once legislators arrive in Washington, Engstrom says, kicking back in his spacious office inside the Chamber's headquarters on H Street. It has to strike first.

That means going in hard for allies like Cochran and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, the kind of Republicans who don't recoil at terms like "appropriations" and "earmarks" — federal spending that economic developers depend on. It also means savaging enemy Democrats, like North Carolina Sen. Kay Hagan and Alaska Sen. Mark Begich, earlier than ever before.

"The bottom line is Tom, Scott and Rob have opted to lead, and take smart, savvy risks," says Mike Murphy, the veteran GOP media consultant who helped produce the Favre ad in Mississippi. "That has made the Chamber the tip of the spear in a lot of critical races."

In Georgia, the U.S. Chamber interviewed several candidates in the Senate race but decided to back Rep. Jack Kingston, putting more than $2 million into the state on his behalf. Kingston, though, lost the Republican primary to businessman David Perdue, a rare loss this cycle for the Chamber. (Photo: Associated Press)

In North Carolina, it has already dropped about $1 million attacking Hagan and propping up GOP nominee Thom Tillis. And it unleashed roughly the same total in Kentucky for McConnell, who faces a stiff challenge from Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes. In Georgia, the Chamber pumped $2 million into the state to aid Kingston, who narrowly lost the Republican Senate runoff this week to businessman David Perdue -- a rare stumble this cycle for the cocksure organization.

The Chamber's political operation is "the teeth in the dog" for the business lobby, Engstrom explains. "Our deal is to have a political program so that there is a hammer, and there is a consequence, and there is leverage and it's aggressive," he says. "But that balances the much larger priority, which is creating certainty for our members, and to remove the threat that we have faced from Washington for the last six years."

Engstrom is talking about the "job-killing policies" of President Barack Obama. But part of the Washington threat, he's quick to acknowledge, comes from within the Republican Party.

Since Obama took office, the Chamber's unabashedly corporate bent – it claims a membership of more than three million American businesses -- has put it at odds with tea party conservatives. The Chamber supported the Wall Street bailout, and then Obama's $787 billion stimulus package and subsequent government bailouts of Chrysler and General Motors.

Those momentous financial decisions in Washington fueled grassroots anger against Obama, Democrats, and establishment Republicans who were accustomed to the occasional compromise. The anti-establishment tea party wave of 2010 brought a Republican majority back to the House – but the small government crowd also brought with them a host of headaches for bottom-line business interests.

Chamber officials say their members were horrified by last year's brinkmanship over the debt ceiling that climaxed in the 16-day partial government shutdown, a stalemate welcomed by tea party Republicans in the House and Ted Cruz, their conservative spirit guide in the Senate.

This year, the Chamber's support for business-backed legislation – big-ticket items like comprehensive immigration reform and a long-term highway bill -- has at times put it on the same side of the political argument with Democrats and labor unions. But those efforts have been met by staunch tea party resistance in the House.

"We don't need to send any more people to Washington, D.C., whose agenda is to vote no all the time, fight with everybody all the time and shut the place down," Studley says.

The Chamber is fed up – and getting even.

"If we see a threat materializing, if we see somebody attacking one of our friendly incumbents like Mitch McConnell or Mike Simpson, then we are required to get in early and frame the debate before its defined," Engstrom says. "If we wait for this narrow strain of self-appointed fake conservatives to set the terms of the debate, establishment versus 'real conservatives' in their mind, then we are going to have a difficult time responding to that."

In a GOP primary in North Carolina's 7th Congressional District this spring, the Chamber battered tea party candidate Woody White with a blistering television ad comparing the Wilmington lawyer to John Edwards, who made his name and fortune in North Carolina as a successful plaintiff's attorney. It outspent every outside group playing in the race by a combined 3-1 margin. White lost.

It did the same in Idaho's 2nd District, going in guns blazing to defend Rep. Mike Simpson against attorney Bryan Smith, who was backed by tea party outfits and the conservative Club For Growth. The Chamber went up with a $500,000 ad buy accusing "trial lawyer" Smith of supporting junk lawsuits. It also brought in reinforcements, tapping Mitt Romney, who had an 86% favorable rating in the heavily Mormon district, to star in a television ad endorsing Simpson (Romney taped the ad in just one take, Chamber aides note with evident awe).

The Chamber hasn't targeted every Republican candidate with tea party billing. Candidates who pass its smell test are left alone. In the Nebraska Senate race, Reed says they were inclined to support Ben Sasse, a health care expert and Harvard grad backed by a constellation of right-leaning figures like Cruz, Sarah Palin and Utah Sen. Mike Lee. But they stayed out.

"Ben Sasse, to my eyes, was the most impressive candidate of this cycle," Reed says. "He reminded me of Jack Kemp. But based on our local partnership, they said we don't need to get in. They said all of the candidates are good, so we decided to stay out. … There is no such thing as a litmus test for us. The only litmus test we have is against those candidate who want to come in and shut the whole damn place down."

Still, the Chamber's primary blitzkrieg and its continuing pleas for immigration reform this summer have only stirred up more fury on the right.

When Donohue issued yet another call for an immigration package earlier this year, saying that Republicans should give up hope of winning the 2016 presidential race if they don't act now, conservatives erupted, accusing the Chamber of supporting amnesty to line the pockets of big business. Radio talk show host Mark Levin fulminated at length on his show about the "Chamber of Crony Capitalism," calling Donohue a "jerk."

"They like laws that benefit them, they like regulations that harm their competition," Levin went on. "That's not capitalism. Call it what you will, that is not capitalism. Mr. Donohue gives capitalism a bad name. … This is the guy that has bought and paid for the Republican leadership. This is the guy who is pouring millions of dollars into these primary campaigns to buy the Republican Party and buy the candidates."

Rush Limbaugh has also gone after Donohue and the Chamber, as have a host of conservative bloggers who were incensed after McDaniel lost in Mississippi. In Georgia's Senate runoff, Kingston lost to businessman David Perdue, a loss that conservative blogger Erick Erickson attributed to the Chamber's support for immigration reform. Perdue highlighted Kingston's Chamber support in a late television ad, claiming that his opponent supported "amnesty" for undocumented immigrants.

But with most big primary contests now in the rearview, one team is clearly winning – and it isn't the tea party.

The U.S. Chamber's emboldened political efforts — ramped up in 2010 after the Supreme Court's ruling in the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case loosened political spending rules for non-profits and trade associations — have been met with alarm by Democrats and their allies in organized labor, even though they sometimes come down on the same side of policy fights in Washington.

"Obviously we are concerned about the increasingly aggressive role the Chamber has played in politics," said Michael Podhorzer, the political director of the AFL-CIO. "Their efforts, like the Koch brothers, are distorting the political process gravely. They are out to undermine all of their political opponents and unions are at the top of that list."

The Chamber is up front about its conservative inclinations. But it is also wary of being seen as an extension of the Republican Party. "We all complement each other," Reed says of the Chamber's relationship with other GOP-friendly groups. "But we aren't an arm of the Republican National Committee. We are bit unique."

Democrats, though, have increasingly fallen out of favor with the Chamber in the Obama era. In 2008, it endorsed 38 Democrats. In 2012, it endorsed five. This cycle, the Chamber has issued 260 endorsements, a total that includes just two Democrats — Reps. Henry Cuellar in Texas and Jim Costa in California. It promises that more Democratic endorsements are on the way, but it will be telling to see how much money the Chamber devotes to saving Democrats in tight races.

The way Engstrom tells it, the diminishing tally is a totem of how the Democratic Party has shifted left under Obama, driving Blue Dog Democrats out by forcing them to answer for politically controversial policies in their districts.

"There has been so much discussion about the war in Republican Party," he says. "That's conventional wisdom, but it's not applied to any consistent manner to the Democratic Party. When the Republicans do it, everyone says, 'Let's go watch and get popcorn and get beer,' instead of looking at the Democrats, where they are purging the party by making them take tough votes."

The Chamber makes its endorsements based on a formula. It sends alerts to members of Congress urging them to vote a certain way on bills deemed essential to the business set — yea on the debt-ceiling hike, for example, or nay on the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill and the DISCLOSE Act. If members of Congress vote with the Chamber on at least 70% of its priorities over time, they usually secure the Chamber's endorsement. Engstrom says not enough Democrats are hitting the mark.

"I wish that we did have 50, 60, 70 Democrats that did vote to support the business community on issues that matter most," he says.

The Chamber's supercharged political efforts have sometimes been a source of tension within its own ranks. There are more than 2,000 state and local chambers nationwide, as well as trade associations, that make up the federation. It's a risk-averse bunch that often prefers to focus on backyard economic development matters rather than partisan warfare.

Some chapters have distanced themselves from the national group in recent years, either out of fear of offending their elected officials or over disagreements on policy matters like climate change. In 2009, several prominent companies, including Apple and Exelon, withdrew their membership from the Chamber — a staunch defender of the oil and gas industries — over the organization's opposition to federal laws that would curb greenhouse gases.

Chamber officials, however, argue that many more local outfits have mobilized politically in recent years to return fire against the Obama administration's economic agenda and regulatory pushes.

"There is a real feeling of strength and unity of purpose in the chamber federation, nationally and here in Michigan," Studley says. "It doesn't mean that every chamber agrees with every chamber. But there is heightened awareness here and across the country that employers must be involved in political action. We have to be proactive."

Billy Canary, president and CEO of the Alabama Business Council, admits that the Chamber's growing political muscle is an unsettling trend to some local branches. But Canary, himself a former Republican National Committee official, believes the necessary steps are being taken.

"If you choose to engage in the political business at the state level and the national level, there is risk," he says. "But in politics, I think it's something that you learn to accept, and you believe it's part of your responsibility."

Tom Donohue — who was once described in The Washington Post as "a bodacious, hard-charging, in-your-face kind of guy" — took over the U.S. Chamber in 1997. Brooklyn-born Donohue, a pugnacious salesman and fundraiser who used to run the American Trucking Association, has transformed the organization, taking it from a $40 million operation to a $250 million lobbying and political behemoth. (Photo: Associated Press)

Before Donohue — who was once described in The Washington Post as "a bodacious, hard-charging, in-your-face kind of guy" — took over the U.S. Chamber in 1997, the organization was regarded as an aimless and underfunded institution without a clear mission. The group even supported Hillary Clinton's health care plan in 1993, infuriating Republicans and many in its own ranks. But since taking charge, the Brooklyn-born Donohue, a pugnacious salesman and fundraiser who used to run the American Trucking Association, has transformed the organization, taking it from a $40 million operation to a $250 million behemoth.

The Chamber roared to life politically in the late 1990s and early 2000s to wage war against plaintiffs' attorneys in Mississippi who were scoring huge verdicts from class-action lawsuits against the tobacco industry that were filed in state courts instead of federal ones. The ensuing battles made tort reform a cause celebre among Republicans and business interests.

In 2002, the Chamber spent heavily against Democrat-backed candidates in state judicial races — and even took the brazen step of warning companies against doing business in Mississippi. The state's then-governor, Democrat Ronnie Musgrove, accused the Chamber of "political blackmail," calling its edict "outrageous, inappropriate and irresponsible."

The business organization waded into federal politics in audacious fashion just a few years later when it announced a national campaign to help friendly Senate and House candidates. The centerpiece of its effort was a campaign to unseat then-Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle of South Dakota. After spending more than $1 million hammering Daschle with television ads painting him an enemy of free enterprise, he lost to Republican John Thune, making him the first party leader to lose his Senate seat in half a century. In an amusing twist, the Chamber also funded an ad that year supporting the South Carolina Senate campaign of Jim DeMint, who would go on to become the intellectual godfather of the tea party movement.

All that was before Citizens United. The landmark 2010 Supreme Court ruling allowed trade associations like the Chamber — a 501(c)6 group, or "business league," under IRS code — to fund expenditures that advocate directly for or against a candidate. And as a non-profit trade association, the Chamber can raise unlimited funds but is not required to disclose its donors under federal election law, opening the door for corporate spending on behalf of candidates in political races.

"What happened with Citizens United, suddenly corporations could fund direct advertising, and didn't need to worry about if it was too close to the line of express advocacy or not," says Trevor Potter, a former chairman of the Federal Election Commission. "But corporations don't want to be seen spending in campaigns, either by their shareholders or their customers or retail operations. So groups like the U.S. Chamber are the perfect vehicles to advance business interests. The source of the money is disguised. So while the Chamber itself may be responsible for the TV ad, the underlying corporate funders are hidden from the public. If the corporations did the ads, they'd have to put their name on it. If they fund it through the Chamber, they don't."

As an umbrella group representing a wide range of corporate interests, the Chamber has long been the largest, most well-funded political player among trade associations, outfits like the National Association of Realtors and the American Chemistry Council. Citizens United made the Chamber an even safer investment for donors and big businesses looking to spend their money efficiently and without disclosure. But they may no longer have the turf to themselves. Potter points out that the Koch brothers organized their main political venture, Freedom Partners, as a 501(c)6 organization with the IRS. "The Kochs are following the Chamber's model," Potter says.

The Chamber embraced the post-Citizens United world with gusto, funding its political activities with money raised separately from membership dues. In 2010, with big business rebelling against Democratic initiatives like the Affordable Care Act, cap-and-trade environmental protections and union-friendly "card check" legislation, the Chamber raised and spent $33 million on political activity, winning 87% of the races in which it endorsed a candidate. The group backed 21 Democrats they deemed friendly. But the Chamber also targeted and helped defeat almost 40 other Democrats, including the outspoken Senate liberal Russ Feingold of Wisconsin.

It was a wave election for the GOP, and like many Republican-friendly outside groups that year, the Chamber crowed about its win-loss record and promised to redouble its efforts the next cycle. It also strengthened its ties with the GOP. Donohue formalized the organization's relationship with Reed, then a consultant, naming him senior political strategist. A savvy campaign veteran and a frequent source for Washington political reporters, Reed was a former executive director at the Republican National Committee and managed Bob Dole's presidential campaign in 1996.

Engstrom, another former RNC official but a lesser-known figure in Washington political circles, was also promoted, given the somewhat clunky title of "senior vice president, political affairs & federation relations and national political director." The lengthy job description reflected Engstrom's political know-how, but also his valuable experience inside the Chamber trenches.

For a decade, Engstrom — a boyish-looking Georgia native who uses the Darth Vader "Imperial March" theme from Star Wars" as his ringtone — had worked on the state-level and grassroots side of Chamber operations, networking with local chambers on legal reform issues and compiling an enormous Rolodex of business and political contacts in state capitals around the country. Those relationships would come in handy.

"As different as their backgrounds are, I look at those two guys as the Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig of the political game," Canary says. "I look at their ability to hit home runs and take risks. You can't be afraid to strike out, you have got to be hitting the ball all the time. Those guys are relentless. If there was a political hall of fame, they would be in it."

A constellation of Republican-friendly groups, including the Chamber, sided with state Sen. Joni Ernst in Iowa's Senate primary. Ernst now faces a general election dogfight against Democratic nominee Bruce Braley for Iowa's hotly contested open Senate seat. The Chamber is vowing to spend heavily in every competitive Senate race. "We are not taking a single Senate race for granted, not one of them," Engstrom said. (Photo: Associated Press)

Despite its bravado and huge budget heading into 2012, that election was a disappointment. The Chamber doesn't play in presidential races and stayed out of the clash between Obama and Romney. And while it hit its goals in House races, the Senate battlefield was a disappointment.

"We got clobbered," Reed says.

The GOP had squandered pickup opportunities in states like Montana and North Dakota, where Democrats successfully framed the races around state instead of federal issues. And for the second cycle in a row, Republicans had fumbled their chance at taking over the Senate by nominating ill-prepared candidates in Missouri and Indiana who were too conservative for independent voters.

But Reed and Engstrom didn't just blame the candidates -- they blamed themselves, and promised to fix it.

"We had learned some bad lessons in 2010," Engstrom says.

A few weeks after the election, the duo booked a hotel in Phoenix and summoned the Chamber's Public Affairs Committee, the organization's political brain trust, to Arizona for a marathon, 75-meeting post-election audit. The committee — an assortment of roughly 50 local chamber CEOs, trade association presidents, corporate leaders, and donors — votes on candidate endorsements, raises money, and provides ground-level intelligence for the national organization. Reed and Engstrom also invited pollsters and consultants to the closed-door session to provide a blunt assessment of what went wrong.

Their conclusion might have been an obvious one, but it would inform every political decision come 2014: The mission from now on, according to Engstrom, was to find and support candidates with "the ability to win and the courage to govern." In other words, tea party ideologues need not apply.

The win-or-be-damned mantra ensured that the Chamber of Commerce would have to engage in elections earlier than in past cycles, even if it meant taking sides in Republican primaries in conservative states and gerrymandered House districts, where the nominee is all-but-assured of election in November.

Never before had the Chamber taken such a step. In places like Mississippi, Alabama and Idaho, it would position it as an enemy of the Ted Cruz wing of the Republican Party.

"We didn't go out and brag on the front page of the New York Times that we were going to pick winners and losers, but we decided to play in primaries where there was a clear choice," Reed says.

The political team also determined that it wasn't good enough to bombard television airwaves with cookie-cutter television ads attacking familiar bogeymen like "Obamacare" or Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid. To court independents and attract new voters in tight races, they figured advertising had to be finely-tuned to the state or House district in play.

"We are designing these campaigns like we are running for sheriff," Reed says. "We are all about driving message to independent and swing voters, and localizing it. We don't need to talk to far right and far left."

Engstrom, the former RNC hand, decided to leverage his long-standing relationships with state and local chambers, mining a national network of business organizations for advice on candidate endorsements and issues. The political team would also work to activate state and local chambers and, hopefully, secure their stamp of approval for U.S. Chamber-backed candidates. Local chamber endorsements would lend a veneer of friendly, neighborhood credibility to their chosen candidates.

Barbour says he saw this dynamic at work in Mississippi, where state affiliates of the Chamber stepped out and endorsed Cochran.

"The chambers have such standing with doctors and small businesses and local economic developers," he says. "I knew that if their name was on it, it would have a whole 'nother level of political muscle and leverage than some super PAC nobody's heard of."

Their first test of the revamped political plan would arrive in August 2013, when Rep. Jo Bonner of Alabama's 1st Congressional District, a safe Republican seat encompassing Mobile, decided to retire. A small army of GOP candidates jumped into the race, and two advanced to the six-week runoff: Bradley Byrne, a state senator backed the party establishment, and Dean Young, a real estate developer and social conservative firebrand. The race didn't fall neatly into the establishment-vs.-tea party narrative favored by the media, but the Chamber's decision was easy. Byrne was the man they wanted in Washington.

Engstrom flew to Alabama and stood with Byrne at an endorsement event that drew heavy coverage from media in the district. "It was a real shot in the arm for us," Byrne says. "They got involved in our race in a big way and it worked, and it was a template for them for other races, and they've been successful elsewhere."

The Chamber then spent $185,000 on direct mail and digital targeting on Byrne's behalf. That money alone, AL.com wrote at the time, "dwarfs Young's entire campaign budget to date." But its message wasn't exactly aimed to the tea party set that many figured would show up in a low-turnout summertime runoff. Instead, the Chamber was telling voters that Byrne supported investments in local infrastructure. In essence, they were telling Republican primary voters in the Deep South that Byrne supported more government spending.

"We pounded them relentlessly with phones, social media and mail," Engstrom says. "It was about the importance of investing in infrastructure and transportation. I surprised myself talking about the need to support Bradley Byrne in a Republican primary runoff in an off-year election in the South talking about investments in transportation and infrastructure. But Mobile is the 11th largest port in America and 60,000 jobs are tied to it directly. And then we talked about funding the I-10 bridge, which is in disrepair."

In the end, 70,000 voters showed up in the runoff election — a 18,000 vote jump from the primary. Byrne won by fewer than 4,000 votes.

Since then, the Chamber has built up an impressive 10-1 record in Republican primaries and in a special election in Florida's 13th Congressional District, near Tampa.

Reed and Engstrom are not foolhardy enough to believe their hot streak will continue into the fall, with far more consequential battles looming against sophisticated Democratic campaigns and outside groups that have been perfecting their messaging and voter contact programs for almost a decade. In North Carolina — so far the biggest target of outside money this year — Hagan has been drowning in negative television ads but still leads Tillis narrowly in most polls.

Engstrom says the 2014 campaign is currently "at halftime."

"There is no dancing in the end zone here," he says. "We are not taking the Eric Cantor lesson. We keep reminding ourselves of the lessons of last cycle where everybody said that Montana, North Dakota, and Missouri were number one, two and three in the pickup column. We are not taking a single Senate race for granted, not one of them."

The Chamber is vowing to play in every competitive and semi-competitive Senate race this election year, from Alaska to Colorado to West Virginia, on top of muscling out tea party House members in their primaries. Last week, they endorsed a GOP challenger to Michigan Rep. Justin Amash, a proud libertarian and reliable thorn in the side of House Speaker John Boehner.

If Republicans do re-capture the Senate in November, the Chamber will, without question, be able to claim a substantial share of the credit. Then it'll be watching intently to see if the chosen crop of politicians live up to its billing.

"What's unique about the Chamber is that we are a 24/7, 365-day a year operation," Reed explains. "The day after the election, we don't vanish. We are up on the Hill watching, lobbying for issues."

As for he and Engstrom, Reed says, "we are not here to exist and sit in a corner office and philosophize about what could have been. We are here to do politics."

CNN POLITICS

Key races to watch in 2014

Democrats have held the majority in the Senate for almost eight years, but as Election Day 2014 approaches Republicans are confident that math and history are on their side.

2014: What's at stake

With the entire House of Representatives and more than a third of the Senate up for election in November, there's a lot at stake in these midterms.